INTERVIEW: Joseph Wambaugh

“The Choirboys drank quietly and speculated about Baxter Slate and felt the closeness of death and stole glances at Roscoe’s gun and thought how near and familiar the instrument always was to men who somehow contract this policeman’s disease. They wondered if the closeness and familiarity of the instrument had something to do with it, or was it the nature of the work which Baxter always called emotionally perilous? Or was it a clutch of other things? And since they didn’t know, they drank. And drank.”

-Joseph Wambaugh, “The Choirboys” (1975)

My introduction to Joseph Wambaugh was of a work he absolutely despises: Robert Aldrich’s 1978 resoundingly unfaithful film adaptation of The Choirboys (1977).

I say unfaithful, but what I really mean is “unfaithful in tone,” and especially in its heightened distrust of the police force as an institution. The film does follow an episodic narrative involving the riotous exploits of a group of hard-drinking, carousing off-duty officers yukking it up and letting off steam in MacArthur Park. It’s just that Aldrich assumes a cock-eyed and buffoonish approach to the characters. The rest of the picture is tainted with juvenile humor and shock appeal, proving that the two would-be collaborators were just stringently opposed in world-views.

Wambaugh fought to take his name off of it after being rewritten, with television writer Christopher Knopf receiving sole credit. But it’s not as if it was a surprise to Aldrich. As something of a preemptive measure, he told Stuart Byron in 1977, “I think Mr. Wambaugh will be very unhappy.”

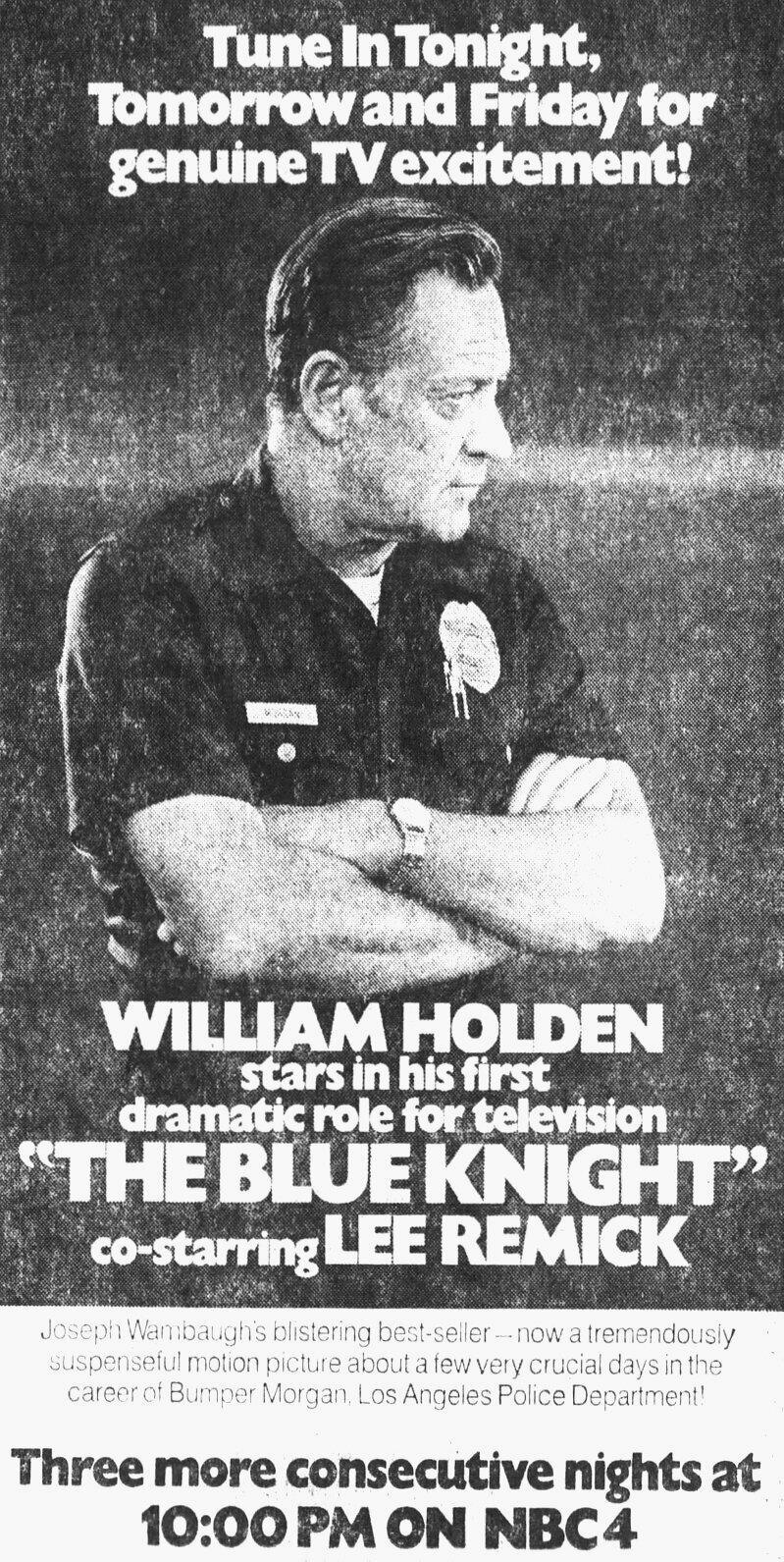

Following a stint in the marines, Wambaugh served 14 years with the Los Angeles Police Department before hanging up his badge to write full-time. It had become a necessity - he had become too famous. This first decade of fiction, the one I’m primarily interested in, runs from The New Centurions (1971) to The Blue Knight (1972) to The Choirboys (1975), The Black Marble (1978), The Glitter Dome (1981) and The Delta Star (1983). There was one work of non-fiction during this period - The Onion Field (1973). It’s heavily influenced and informed in structure by In Cold Blood. This is not by accident, as it was encouraged by Truman Capote after a backstage introduction before an appearance together on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Wambaugh generated a lot of non-fiction in the 1980s, turning back to fiction in the ‘90s and concluding - for the time being - his publishing career with a sort-of throwback series to those early novels: the five Hollywood Station books that began in the aughts.

Without Wambaugh, you wouldn’t have James Ellroy, who infamously (and gleefully) calls him a “right-wing absurdist.” And without Wambaugh’s NBC anthology series Police Story (1973-1978), you wouldn’t have Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue, Homicide: Life on the Street, and countless others. But Wambaugh’s work, at every turn, is governed by a virtuous credibility thanks to those tireless years on the force. He’s not re-contextualizing or remixing narratives gleaned from other books or film and television, but from a chunk of his life that saw him dealing with the dangerous realities of the job - complex puzzle-piece cases, sudden outbursts of violence - and observing all of their attendant effects on himself and fellow officers.

I spoke with Joseph Wambaugh a couple of years ago on St. Patrick’s Day.

AARON GRAHAM: How did The New Centurions (1971) come about? You were still working when it was published?

JOSEPH WAMBAUGH: I wrote it without anyone knowing about it. I doubted it would ever get published, but wanted to give it a try. I told no one - not even when my publisher accepted the book and paid me the grand sum of $2000 or $3000 in advance. I thought that was all the money I’d make. Then, I got a frantic phone call. It was picked up as the main selection for the Book of the Month club, and in those days, that was a very big deal. I think the advance on that was $50,000. And in 1971, $50,000 was a huge amount of money - you could buy a house, and a pretty good one. Then, of course, the word got out, and everyone knew - an LAPD detective had written a novel that was a Book of the Month club selection. Everyone wanted to know about it. So it was immediately snatched up by Columbia Pictures and a movie starring George C. Scott, coming off his Oscar win with Patton.

AG: When did you know you had to quit the police force?

JW: I was on Carson all the time, and pretty soon, my police partner (Richard Kalk) was opening the car door of our detective unit. I said that’s it - when my partner is opening the door for me, I gotta go.

AG: Famously, Robert Towne did a draft of The New Centurions.

JW: Yes, the great Robert Towne - Chinatown. He was the top screenwriter of the day. He took a pass and wrote a script of The New Centurions, but got into arguments with the producers and bailed and didn’t want his name on the final product. His name wasn’t, of course. I was still a working detective and just amused at the motion picture shenanigans. I did meet with Robert Towne at a restaurant so that he could pick my brain. I got to know him. He told me of the disputes with the director and producers. He was a good guy.

AG: What were the origins of Police Story?

JW: As a series, Police Story was suggested to me by David Gerber, the Executive Producer, when I was still a cop. It was my idea to make it an anthology - at that time and to this very day, anthologies are not very successful in general. But I was convinced that was the way to go. Without a continuing family of stars, we could have very original shows each week. We could kill off main characters and do anything we wanted to. David Gerber was a great salesman. He convinced NBC that an anthology would work, and it did.

David Gerber really was the impetus behind it - he was a television genius. They would send me the scripts each week. I would go over them, do some editing, throw some of them out. I created some havoc of my own because I wanted a different kind of police show. I didn’t want Jack Webb. I wanted something totally different. I didn’t want a lot of shoot outs. I didn’t want a lot of chases. It used to drive poor David Gerber crazy, because he’d have to go to NBC and explain to them why we were giving them a “sensitive” show - a character study about how the job acts on the cop, rather than how the cop acts on the job.

It just so happens that the other story editors were Irish. Liam O’Brien, Edmond O’Brien’s brother. And Liam’s nephew was Ed Waters. Three of my grandparents came from Ireland, so David Gerber, in frustration each week, would refer to us as the “Irish Art Theatre.” He’d beg us to give him a story with blazing guns and screeching tires. We would always resist that.

There was one episode called The Wyatt Earp Syndrome [Season 1, Episode 20]. I particularly liked it. But it was originally called The John Wayne Syndrome. Somehow, John Wayne’s production company got wind of it and didn’t want us calling it that. Well, it just so happened that in the Los Angeles Police Department, at that time, there was something really called a John Wayne syndrome. It referred to the stage of a cop’s life where he’s had a couple of years on the job and started to get “badge-heavy.” He started throwing his weight around, swaggering like… John Wayne.

The entire story was about how the job acted on him. At the end of the show, he was sitting in his apartment alone, his wife had left him, and he had just gotten off of his tour of duty. He was crying, just weeping. That’s how it ended. After that, a lot of other shows copied the style - started doing more sensitive shows.

Tony Lo Bianco was in one [Firebird, Season 3, Episode 18], where he played a helicopter pilot. He was burned pretty badly, and that was based on a true incident in the LAPD where a helicopter observer was trapped upside down in a police helicopter. He was on fire - his face, his hands. He was badly burned. The episode was basically how he dealt with that. When he gets out of the hospital, he has a very poignant meeting with his small child - the child basically couldn’t recognize daddy, he’d been burnt so badly. It was about overcoming the fear of the child. But Lo Bianco didn’t want to wear the burn make-up. He played it wearing a beard, with just a little scarring. It just didn’t work - I was really angry at that one.

AG: You appeared in one yourself, with Jan-Michael Vincent. [Incident in the Kill Zone, Season 2, Episode 12).

JW: Nobody ever asked me to get a SAG card after that, and I wasn’t offered any starring roles in any feature films. I just did a little appearance for David Gerber, as he wanted me to appear in one.

Producers sent me a black-and-white 8x10 photo of myself in the role, as a SWAT officer. There I was in SWAT gear, holding a shotgun, displaying what I thought was a look of intensity. At the bottom of the photo, producers put a little caption: “I shouldn’t have eaten those prunes this morning.”

AG: Your real-life partner, Richard Kalk, fared better in that respect.

JW: Yes, my detective partner. We were detectives together for six years. He did get a SAG card and played in a lot of stuff, including one I saw on TV last night - Shampoo, with Warren Beatty. He bought himself a nice house from all of the royalties from his acting career.

AG: Did you spend a lot of time on set?

JW: I didn’t spend a lot of time on set or location. Richard Kalk did - he was constantly the technical advisor for Police Story and some of the movies made from my work. The New Centurions, The Blue Knight. But I didn’t go on the ground much.

I was on location and on set every moment for The Onion Field (1979) and The Black Marble (1980). I was the screenwriter who did the adaptations. But the real reason I was on set constantly was that my wife and I raised the money. They were not studio-financed. I think The Onion Field holds up pretty well, as does The Black Marble.

I mean, that was full time, mainly because I was watching the money. We had so little. We made those two for peanuts - we were on a tight budget. That took all my time and energy. I never wanted to do that again. The stupidest thing a person can do is put all of their money into a film production.

AG: Did you get caught up in writing other screenplays? Unproduced?

JW: I was hired to adapt a few others. They never got produced - typical for a screenwriter. Very little of what screenwriters actually write gets on the screen, large or small. I did some of that - not much. I was busy writing books. I wrote 21 books, so it took up my most creative energy.

AG: What’s your writing schedule like?

JW: Basically the same, when I’m writing. I do my workout in the morning and then start writing for as long as I can - sometimes 5 or 6 hours. That’s usually max. Once in a while, I can go 8 hours or more. I still do the same thing, but as an old man now.

AG: Why did you decide to go back to fiction after a long period of non-fiction?

JW: Non-Fiction is too hard to come by. As the years went on, and some of the non-fiction books became big best-sellers - like mine - everybody that you talk to just starts thinking big budgets. Or thinking lawsuits.

Every non-fiction book I wrote got me sued, except for two. The one that didn’t get me sued back in the day was the one that took place in England [1989’s The Blooding: The Dramatic True Story of the First Murder Case solved by Genetic Fingerprinting]. I went to England for a few weeks and researched and brought a couple of the British cops back with me to Newport Beach. The reason I didn’t get sued on that one is that in Britain - and the rest of the civilized world - you sue someone at your peril. Because if you fail at your lawsuit, the successful defendant can retrieve court costs or at least part of them. This discourages frivolous lawsuits. In the US, we have no such system and everyone can sue with total impunity - make your life miserable, make you spend a fortune. It’s legal to blackmail. The US is run by lawyers - Congress is full of lawyers, and they don’t want to change that system. It’s just such a misery - no more non-fiction for me.

I think I’ve run the gamut on the Hollywood Station novels. I’ve done 5. I’m still trying to get them on TV. That’s what I’m doing right now, writing scripts. I know it could be a great series. And I just keep knocking heads and doing my best. Don’t know if I’ll ever make it - but what else I’m going to do.

AG: What about another - proper - adaptation of The Choirboys?

JW: The Choirboys was made into a rotten motion picture by Lorimar. It deserved to become a good movie. I wrote the original screenplay. But Robert Aldrich had it rewritten by Christopher Knopf, a big name in the screenwriting business.

Aldrich and I could never get along. When the script was finished by Knopf, the technical advisor on the set - an LAPD cop - phoned me. “You know, your name is on this screenplay in front of me, and I know you didn’t write this shit.” So that’s when I found out. I sued immediately while still in production, took my name off it. It’s a horrible movie.

POST-SCRIPT

Back to Robert Aldrich and His Choirboys. I’m still fascinated by it, despite all of the acidity and ludicrousness on display. I saw it late at night, maybe 1 am, on Bravo TV (before that network switched formats to Reality TV). After the first hour, inexplicably, the movie began again: its opening scene of 19-year-old fire team leader (played by James Woods) facing an ambush in Vietnam. I thought, logically, maybe this is another flashback, but I soon caught on that there was the equivalent of a station error, and the entire picture was starting again. Whatever its faults and pitiful reputation, it kept me hooked all over again until lurching to its conclusion.