DEATH PLAYED THE FLUTE (1972)

“You Want a Guide … or a Gunman?: The Confusing Authorship and Bizarre Re-Release(s) of Death Played the Flute (1972)"

Death Played the Flute (1972)

Directed by Luigi Petrini / Angelo Pannacciò

also known as: Lo ammazzò come un cane… ma lei rideva ancora (Italy); Requiem for a Bounty Hunter (USA; re-release)

OPEN ON: Five abject ruffians led by the vile Ramson (Antonio Molino Rojo) as they chaotically ambush the Red Ranch, an idyllic spread in the countryside, owned by absent patriarch Nick Barton (Michael Forest). The quintet rape his daughter - Suzy (Susanna Levi) - until she’s in a catatonic state and then slaughter his father and wife. An unmerciful brute named Kimble (Giuseppe Cardillo, aka Steven Tedd, a facsimile of Elvis Presley in Charro!) comes along for the ride but doesn’t partake in such wretched brutality. Still, Suzy does make a mental note of his trademark amid her unfathomable horrors: the almost dissociative tic of melodious flute-playing, an instrument tied to a string around his neck. In the next couple of scenes, Kimble - nickname: Whistler - will quit the bandits (which includes a member resembling Tomas Milian, in wooly knit-cap), ruefully declaring he’s “there to rustle cattle, not kill." He won’t get off so easily.

The chiseled, bronzed Michael Forest (or, “Forrest” in the credits), early Roger Corman regular and frequent ‘60s television western guest star, plays Nick Barton as a White Hatted beacon of suaveness and unwavering integrity. Discovering the unspeakable terrors that have transpired in his home, and ensuring the now-mute Suzy has her fiancee (Franco Borelli) to take care of her, Barton rides off in pursuit of well-deserved revenge. He runs into a now riding-solo Kimble, and a shaky deal is struck: for one thousand dollars, Kimble will assist Barton in finding the outlaws who have removed his family’s peaceful existence. (You wouldn’t be the first to recognize this as the skeletal plot of Giulio Petroni’s Death Rides a Horse, from 1967.)

Kimble does a bit of side business in his sojourns with Barton, including shooting and delivering a bushwhacker corpse for a quick $600 payday. (This scene so clearly captured on the western film sets of Cave Studios in Italy.) And in the film’s most harrowing display of depravity, and despite suggesting a moral code with his refusal to be part of the opening scene’s violent activities, Kimble sexually assaults a bordello worker. (Him: “Strip, honey.” Her, pleading, after she does: “Why do you always want it like this?”).

A curiously flimsy plot mechanic: Barton never really grows suspicious of Kimble, and he remains oblivious throughout, failing to speculate on why Kimble knows so much about the men who murdered his family. But as Production History will dictate further down, it’s a wonder that this is the extent of all that’s perplexing.

At the close, in a satisfactory about-face, Death Played the Flute makes it all about the disorienting moment of clarity on the face of Susanna Levi as Suzy Barton. She has an instant callback to her troubled time, secures a weapon, and provides cathartic and balletic slow-motion shotgun blasts to Kimble, the man who abided her tormentors and almost got away with it. (He just could not leave his hands off that flute before departing Red Ranch.) Nick Barton doesn’t even have a final embrace with his daughter; the transgressive attempts to enact retribution were all for naught. Suzy Barton rides away, now blissfully autonomous.

A Man is made of love and fear /

Fear of finding nobody near /

When daylight turns /

The sunshine in the heart may die

Ann Collin sings the chintzy and awful theme song - “A Man is Made of Love” - with lyrics by A. Nohra. Despite the pedigree, it's mind-numbingly asinine. Collin was a frequent vocal contributor to the spaghetti western, having already recorded similar work for Sergio Corbucci’s Ringo and His Golden Pistol (1966), Giulio Questi’s Django Kill… (1967), Giancarlo Romitelli's His Name Was King (1971), and Deaf Smith & Johnny Ears (Paolo Cavara, 1973). A. Nohra is Audrey Nohra Stainton, seasoned lyricist of some pure-pop-gold in the Italian exploitation market, including at least three with Ennio Morricone: The Hills Run Red (1966), Run Man Run (1966) and The Ballad of Hank McCain for Machine Gun McCain (1969). The rest of the score by Daniele Patucchi is a lot of patchy fuzz guitar cues and primitivistic, atonal droning - especially amped up when Kimble attacks the prostitute.

Let’s extrapolate a little on the headache-inducing confusion over directorial credit and post-production insanity of the 1972 Italian-financed release, Death Played the Flute, including details of its 1979 re-release. At least as I’m able to understand it because things get complicated, quick.

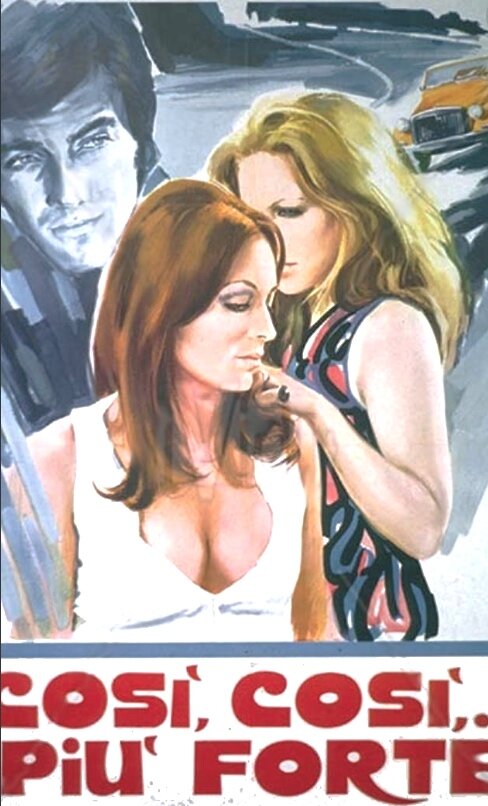

From what my nominal research determines, the year is 1971 and Angelo Alessandro Pannacciò, or Elo Pannacciò, is an Italian film producer and writer who has just cranked out two erotic psychodramas with very similar premises, Così, così... più forte (1970) and La ragazza dalle mani di Corallo (1971). (Rough English translations, respectively: So, So… Stronger and The Girl with the Coral Hands.) But he’s really itching to direct. Naples-born Susanna Levi is his 23-year-old paramour and lead actress. In both films, Levi plays the beguiling catalyst for complicated affaires de coeur with men and women, the two genders so unable to contemplate existences without her that they would rather perish fiery deaths than to share her charms, as conveyed in the car-crash finale of Così, così... più forte.

Side-note here: La ragazza dalle mani di Corallo proves too tough to locate, at least for the time being, but I did find an Italian-Language, non-English-subtitled, but Greek-subtitled VHS-derived transfer of Così, così... più forte. The synopsis for La ragazza makes it sound comically identical, albeit with differing and alluring cast members for Levi's make-out sessions. All of this is a long-winded way to say I’d wager a calculated guess that the second of these two sexually explicit pictures is also full of frivolous, contemporaneously-hip and kaleidoscopic montages with two women/one man set to the sensuous and gentle bossa-nova music of Death Played the Flute composer Daniele Patucchi. As such can be gleaned from Così, così, scenes alternate either between melodramatic moments of petty squabbling or extended sexual escapades that leave little to the imagination other than the up-close specifics of hardcore insertion. There are numerous instances of the two ladies (Levi, Margaret Chaplin) cavorting languidly in bed after visiting museums or rock-show happenings, or another in which the male tennis pro (Alessandro Masselli) and Susanna Levi awkwardly screw on a sandy beach. For the climax, after a violent altercation with the man that involves the authorities, everyone makes nice and participates in an energetic threesome before grappling with their inharmonious living situation. Then they decide to off themselves. You have to ask yourself: What was Angelo Alessandro Pannacciò silently exorcising in these written treatments that were ostensibly big-screen free-love showcases for a then-girlfriend and, presumably, a fame-seeking young actress?

At any rate, Pannacciò wasn’t a filmmaker. At least, not yet. Luigi Petrini, a somewhat experienced but still relative novice, directs both films. Before this, Petrini has three credits to his name - a realistic marriage drama/One from the Heart (Una storia di notte, 1964), a rock-n-roll beach comedy (Le sedicenni, 1965), and a crime thriller (A suon di lupara, 1968). Then, in earnest, he directs the two erotic Susanna Levi projects with Pannacciò’s involvement. Petrini/Pannacciò start a company - Universalia Vision. I can’t say for certain whether or not they were considerable financial successes in Italy, but they must have been positive, creative experiences for all involved as Pannacciò and Petrini next team-up for a western that the former has written, entitled Lo ammazzò come un cane… ma lei rideva ancora - aka: Death Played the Flute. They shoot much of the film in Italy at the infamous cheapie Cave Studios, owned by Gordon Mitchell, and also schedule days in Spain at Balcázar Studios in Esplugas City, near Barcelona. It might be before the unit moves to Spain, but it’s around this time that Pannacciò and Petrini fall out. Petrini may have quit here, but maybe not. Read on.

On the heels of wrapping Death Played the Flute at Balcázar Studios, Pannacciò quickly enters production as Producer on a second spaghetti western - Manuel Esteba’s Una cuerda al amanecer (You Are a Traitor and I’ll Kill You!). Universalia Vision is again responsible. Traitor doubles up on the same Spanish locations used for Death Played the Flute, and also brings back mutton-chop side-burned actor Giuseppe Cardillo (also known under the more anglicized name Steven Tedd). Susanna Levi sits this one out. Production commences on Traitor, production finishes.

It could also be here on the admittedly indeterminate timeline in which Pannacciò and Petrini ruin a previously amiable partnership. At any rate, it’s here that the aspirational Pannacciò gains whatever bravado he needs to take the next step and yanks post-production duties from Petrini, either due to having experienced on-set frustrations with Death/Traitor or, maybe more simply, because Petrini just did not submit enough footage for a feature-length release. (There’s informed speculation that Pannacciò shot an extra scene before the 1972 version with the readily available cast - girlfriend Susanna Levi and her character’s fiancee, played by Franco Borelli - to pad out the running time to a still slipshod 74-minutes. This bit of business admittedly does stick out like a sore thumb: The duo leaves Red Ranch and visits a neighboring town, in the hopes of finding Nick Barton. They do not find him.)

Anyway. Pannacciò asserts control on all matters. Death Played the Flute and You Are a Traitor and I’ll Kill You! hit theatres in 1972 and are instantly forgotten. Angelo Pannacciò is credited as director on Death. Manuel Esteba is listed as director on Traitor. Luigi Petrini isn’t listed anywhere.

Death Played the Flute is a dark film pictorially, with fleeting moments of cooperating weather with the rest drowned in overcast skies. Petrini choreographs the gun battles adequately, but it’s the close-quarter attacks and brawls that are his specialty, favoring subjective camerawork for both violent pursuer and victim. If you ran the fight sequences from Death Played the Flute next to the one instance of physical force in Così, così... più forte, there is no question that despite the signed author of Angelo Pannacciò, this really is the work of Luigi Petrini. They are interchangeable if it were not for the actors and period vs. mod clothing.

FAST-FORWARD. In 1979, Death Played the Flute is re-released in an 84-minute cut. It’s re-titled Requiem for a Bounty Hunter. (This will be the title given to its only VHS release, in Greece, although the credits will be wrong and it’s the 74-minute version that Pannacciò first prepared.) It seems that in 1978, Angelo Pannacciò may have cobbled together some cash and shot some extra material, including isolated hardcore inserts. It is recorded in Thomas Weisser’s guidebook - Spaghetti Westerns: The Good, the Bad and the Violent: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Filmography of 558 Eurowesterns and Their Personnel, 1961-1977 - that Death Played the Flute (and maybe parts of Traitor) was purchased by an unscrupulous distributor and padded with pornography for something called Porno-Erotic Western, also released in 1979. But in reality, Pannacciò was responsible for both the re-release and the X-rated feature. It’s disputed whether Porno-Erotic Western even contains segments from Death Played the Flute since it hasn't turned up since 1979. (Also, while I’m here, I’d like to correct another egregious item from Weisser’s book: Mel Welles, Mushnik from The Little Shop of Horrors (1960) and nomadic offbeat director of Lady Frankenstein (1971), has nothing to do with any of this. Pannacciò merely chose anglicized moniker Mark Welles for the re-release “Directed By” credit, maybe as a misguided homage to Orson.)

What’s not disputed is that the Greek VHS release - put out by a company in Greece called Hi-Tech Video - inexplicably contains the opening credits for Porno-Erotic Western. Ray O’Connor (really, Remo Capitani), Thomas Rudy, Laurence Bien and Alceste Bogart appear nowhere in Death Played the Flute. Maurizio Centini was only the Director of Photography for post-1972 re-shoots; by most accounts - and logic dictates - the original DP was Girolamo La Rosa (as he shot Così, così... più forte and You Are a Traitor and I’ll Kill You!). Further complicating matters: the Internet Movie Database has the DP listed as Jaime Deu Casas, a camera operator on Mario Bava’s Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970). The credits are such a mess that Susanna Levi doesn’t receive billing.

Following Death Played the Flute, it takes a few years for Petrini to get another job, but he does eventually, releasing - in 1974 - the ridiculously-named service comedy Scusi, is potrebbe evitare il servizio militare?… No! (Excuse Me, Could Military Service Be Avoided?… No!). By this time, Pannacciò is a horror filmmaker, responsible for Sex of the Witch (1974), co-starring Levi and future I Spit On Your Grave actress Camille Keaton. And then something called The Return of The Exorcist, a cheapie knock-off of the William Friedkin picture, starring Richard Conte.

By the start of the next decade, even though their paths don’t cross, Luigi Petrini and Angelo Pannacciò are both loosely involved in sporadic titles in the then-burgeoning Italian hardcore pornography market. There’s no production activity for either after 1988, with Petrini last listed as co-director of a travelogue for the Aurora Express, a first-class railway service once linking Rome to Naples.

An Italian online message board dedicated to Spaghetti Westerns has it that Luigi Petrini finally sees the 74-minute version of Death Played the Flute, shortly before his death in 2010, courtesy of an Italy-based scholar. Although the film is signed Angelo Pannacciò - or, to be accurate, Mark Welles - Petrini claims responsibility and remembrance over every shot.

It’s a forgotten, arguably disreputable movie that isn’t very good and looks atrocious on any current high-definition television, even if you were to spend the considerable time to procure a grey-market disc captured from a 1980s VHS originating from Greece. But credit matters and the work of Luigi Petrini matters, and I’ve moderately enjoyed the few I’ve been able to see. His work encompasses a favorite phrase I’ve probably stolen from somewhere, but don’t remember where. His films are Not Without Interest.